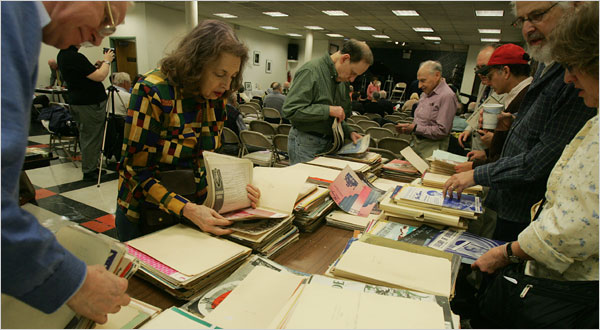

Members of the New York Sheet Music Society going through a vendor’s files to search for favorites before a meeting. Photo by Hiroko Masuike for The New York Times

There are not many organizations in New York that stage singing performances as part of their regular meetings – especially not a performance by someone like Marni Nixon.

Ms. Nixon may not be a familiar name to everyone. But anyone who has seen “West Side Story” or “My Fair Lady,” two of Hollywood’s classic musicals, has certainly heard her: Ms. Nixon provided the singing voices for Natalie Wood and Audrey Hepburn in those films.

So Ms. Nixon, who has built her reputation in popular, opera and classical music, was a fitting guest at the most recent gathering of this particular group – the New York Sheet Music Society.

The society’s mission is to keep the great American songbook alive, to pass along the artistry, lyrics and melodies of the country’s rich treasury of musicians like the Gershwin brothers, Porter, Arlen, Mercer, Rodgers, Hart and Hammerstein.

“Alas, the list is virtually endless!” said Elliott Ames, a member of the society’s board, who wore a tie patterned with musical bars from “Rhapsody in Blue.” “The meetings are alive with music.”

The society began in 1980 with a small but dedicated group that met to exchange sheet music and stories.

Many of the society’s members are performers and songwriters or are related to musical luminaries and, as Mr. Ames puts it, “fervent in their desire to protect our musical heritage.”

Every meeting of the society, which has about 400 members, opens with a flea market, where sheet music, old recordings and memorabilia are traded and members share news about upcoming performances. It was at the group’s first meeting of the season last month, held in the theater of Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians on West 48th Street, when Ms. Nixon sang “I Could Have Danced All Night” and “Wouldn’t It Be Lovely” from “My Fair Lady,” as well as “Getting to Know You” from the “The King and I.”

“I never knew about it before,” Ms. Nixon, 78, said. “I think it’s spectacular; it’s major nowadays that people preserve this music.” Ms. Nixon, who performs, teaches singing out of her Upper West Side apartment, and bought the two-bedroom apartment above hers to hold her collection of sheet music and memorabilia.

The society’s president, Linda Amiel Burns, was raised in Manhattan surrounded by songwriters. Her father, Jack J. Amiel, owned the Turf and Jack Dempsey’s, two restaurants, both long gone, where many songwriters passed the time. Both were in the Brill Building, on Broadway at 49th Street, which was originally built as an office building for brokers and bankers but was rented out to music publishers during the Depression.

To promote their new songs, publishers would send down sheet music to try to pique the interest of those gathered in “the songwriters corner” at the Turf, where the walls were decorated with sheet music. “Ella Fitzgerald loved the cheesecake; she used to come in all the time,” Ms. Amiel Burns said.

“My father used to drill me,” she recalled. ” ‘Linda, that songwriter at that table is Ruby Bloom; what did he write? That one is Sammy Cahn; what did he write?’ I loved those guys. I was the little princess at the Turf.”

Mr. Amiel, who was from Greece, shared a similar immigrant story with many of the songwriters who were first- and second-generation Jewish newcomers trying to make it in New York. Ms. Amiel Burns has a trove of items that reflect a life surrounded by music. She still has the lyrics from “Tea for Two” that the songwriter Irving Caesar, a member of the society, wrote out for her. She treasures a photograph of her with Cahn, a lyricist who won four Academy Awards, and Jule Styne, who wrote the scores for “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” and “Gypsy.”

Over a recent lunch at the Friars Club in Manhattan, Ms. Amiel Burns pulled out a stack of sheet music from her collection, many signed by their composers and lyricists. “These covers are such great art,” she said.

“The Streets of Old New York,” shows a master of ceremonies drawing back a theater curtain to reveal a Manhattan street scene. Some of the other titles include “She Read the New York Papers Every Day” and “I DonÕt Want a Home in the Country (City Life’s the Only Life for Me).”

“These sheets are the history of New York,” said Ms. Amiel Burns, who also runs the Singing Experience, a performance workshop, where after four classes, she said, her students are ready for the city’s cabarets. There are songs about the Flatiron Building, Tin Pan Alley and Broadway. Others are about falling in love, feeling lonely on a cloudy day and finding happiness when all hope seems lost. They wrote a few songs about pianos: “Ain’t My Baby Grand,” “Which? Grand Baby or a Baby Grand,” “I’ve Got a Grand Baby With a Baby Grand” and “Movin’ Man Don’t Take My Baby Grand.”

Following in her father’s footsteps, Ms. Amiel Burns opened the Symphony Cafe in 1988 on Eighth Avenue at 56th Street, which displayed items from the Songwriters Hall of Fame, including a top hat given to Fred Astaire by Cole Porter, Jimmy Durante’s fedora, the ruby slippers Judy Garland had made for the songwriter Harold Arlen and one of Elvis Presley’s guitar picks. The cafe closed in 1993.

The society’s sheet music collection is vast – just how vast is difficult to determine, partly because members keep their own personal collection.

Sandy Lowe Marrone, a vice president of the society, has an overflowing archive of 200,000 sheets dating to the 1800s in her home in Cinnaminson, N.J., which she organizes by theme and provides to collectors and movie producers.

When asked the average age of its members, Ms. Amiel Burns joked, “Death.” She corrected herself, “Excellent long-term memory.”

“So many guys are gone,” she said. Members who have died include Burton Lane, who discovered Ms. Garland; Mitchell Parish, who wrote “Stardust”; and Johnny Marks, who wrote “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

Among current members are Charles Strouse, who wrote the score for “Bye Bye Birdie”; Karen Lynn Gorney, whose father, Jay Gorney, along with Yip Harburg, wrote “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”; and Ervin Drake, who wrote “It Was a Very Good Year,” which was recorded by Frank Sinatra.

“We need younger members!” Ms. Amiel Burns said. A yearly membership costs $50, which includes a singing performance at each of the society’s nine scheduled meetings, as well as monthly newsletters; it makes the club, in Ms. Amiel Burn’s view, “the best deal in New York.”

“It’s about nostalgia and keeping this music alive,” she added. “We remember these songs because of the lyrics – they tell a story in their harmony, melody – and because they say, ‘I love you.’ ”

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/03/nyregion/03sheet.html